Peoples of Ancon

Peoples of Ancon

Archaeology of Peru from a journey around the world

At the end of the nineteenth century, the Corvette Vettor Pisani’s epic voyage around the world reaches the coasts of Peru. On board there are two young officers from Modena, Antonio Boccolari and Paolo Parenti, who take advantage of the stop in Ancon to explore a pre-Columbian necropolis. From that archaeological walk they will bring home human remains and objects linked to the funerary ritual and will donate them to the city museum. The rediscovery project of this collection puts humanity at the center: not only that of the peoples of Ancon, reconstructed through anthropological investigations into the human remains from the necropolis, but also that which emerges from the profiles of those who participated in a journey to circumnavigate the globe, which at that time still had the flavor of enterprise.

1 Travel tales

Setting sail on 20 April 1882 from the Port of Naples, the Royal Corvette Vettor Pisani started its fourth and final oceanic campaign, which would lead it to sail over 40,000 nautical miles. In addition to the official account of the expedition, based on Commander Palumbo’s unpublished report, there are also various ship logs which chronicle the Vettor Pisani’s voyage around the world between 1882 and 1885. Lieutenant Chierchia’s diary deals in particular with marine zoology collections, Lieutenant Serra’s focuses on meteorological observations and hydrographic surveys carried out along with Lieutenant Marcacci. Even Prince del Drago, who participated in the expedition on behalf of the Italian Geographic Society, and Lieutenant Pandolfini published historical-ethnographic reports and insights on the lands visited. Lieutenant Tozzoni left a series of notes and a photo album of the trip, which collected both images bought in the various countries visited and photographs taken by Commander Palumbo.

The officials on board, Aden 1885. Photographic Archive Imola Museums, Tozzoni photographic fund.

1 R. Pericoli 2 R. Pandolfini 3 C. Marcacci 4 G.C. Bertolini 5 F. Chiozzi 6 R. Caniglia 7 A. Boccolari 8 R. Della Torre 9 G. Palumbo 10 F.G. Tozzoni 11 C. Zuppaldi 12 U. Cagni 13 F. Milone 14 G. Chierchia 15 G. del Drago 16 P. Parenti 17 E. Serra

Display case:

Nautical instruments belonging to Francesco Giuseppe Tozzoni, 19th century, Imola Museums, Palazzo Tozzoni.

2 An on-board laboratory

The Vettor Pisani’s expedition saw military, political and commercial motivations intertwined with scientific purposes. The Ministry of the Navy, in a climate of growing awareness of the importance of oceanographic research, had in fact ordered that soundings and hydrographic surveys be carried out during the expedition and that a collection of marine zoology be established.

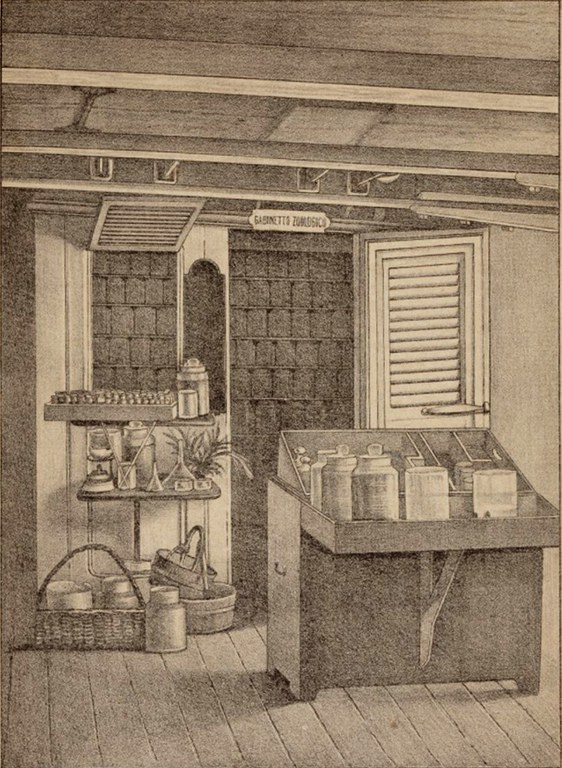

The collection was entrusted to Lieutenant Gaetano Chierchia. For this purpose, the officer was sent for three months to the International Zoological Station in Naples, where he would receive the “necessary special instruction” from Prof. Anton Dohrn, founder and director of that institute, and from the conservator Salvatore Lo Bianco. In his logbook, Chierchia reports a detailed description of the laboratory set up on the ship and of the instruments used to collect, study and preserve the zoological finds during the voyage. The collection was comprised of a total of 350 glass bottles, 1,140 tubes and 25 zinc cases full of animals, 166 species of plants and algae, 4 cases with shells, dried animals and samples of the seabed.

On the wall:

Reconstruction of the zoological study set up on board the Vettor Pisani by Gaetano Chierchia. Containers, instruments and furnishings were kindly loaned by Annalisa Lusetti and Gianluca Pellacani. The exhibition also includes glass containers from the Museum of Zoology and Comparative Anatomy of the University and Modena and Reggio Emilia and from the Franzoni Pharmacy collection owned by the Civic Museum.RMONITOR

The Zoological Station of Naples. Founded by the German zoologist Anton Dohrn in 1872, it was an independent international research institute in marine biology. It functioned as a “science factory” made up of many different disciplinary sectors. Governments, universities and other institutions could rent a study table there for their biologists.

Display case:

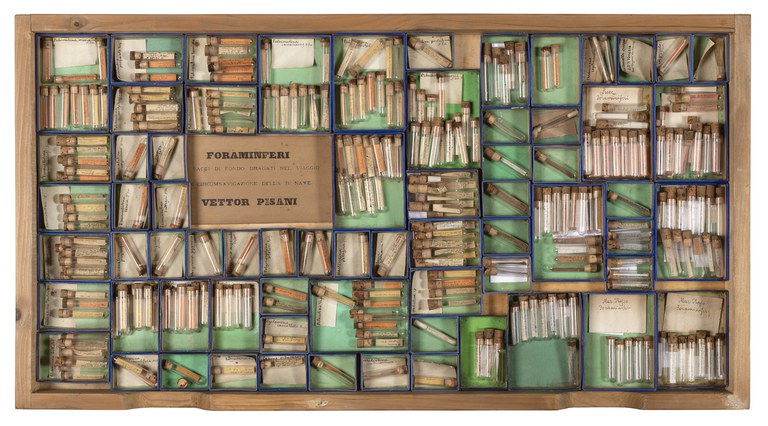

Foraminifers from bottom samples dredged during the voyage of the Vettor Pisani. Museum of Zoology and Comparative Anatomy, University of Modena and Reggio Emilia.

Display case:

Exotic souvenirs collected by the officers of the Vettor Pisani and later included in the collections of the Civic Museum of Modena:

- Opium pipe with lacquered wood stem, glazed ceramic knob and applique with ideographic inscription, China, 19th century.

- Ivory travel cutlery set, China, 19th century.

- Hookah, China, 19th century.

Display case:

Model of a boat from Pernambuco, Brazil, 19th century, Civic Museum of Modena, Boccolari donation.

Monitor

Ensign Giuseppe Tozzoni, in addition to writing a diary and collecting objects during the expedition, put together 135 images in a photo album, mostly of landscape views, but also ethnographic portraits, and, to a lesser extent, photographs related to episodes that occurred during the trip.

3 The Boccolari-Parenti Zoological Collection

The interest sparked by Chierchia’s research pushed some officers to undertake naturalistic collections of their own. The two men from Modena, Paolo Parenti and Antonio Boccolari, put together zoological collections that enriched the university museums of Modena. Many of these specimens were collected during excursions or hunting trips, others were gifts received from Italian immigrants. A few were purchased from animal agencies for zoos, or in markets or along the roads. On board the ship, the smaller animals were kept in glass jars, the larger ones in cases lined internally with zinc.

Despite the care taken in preparation, not all of the finds reached Modena intact, and only part of the 217 specimens collected remain in Modena’s university museums.

On the platform:

Spider monkeys, iguana, geese, seal skulls and orca skulls. Animals from the Boccolari-Parenti Zoological Collection loaned by the Museum of Zoology and Comparative Anatomy of the University of Modena and Reggio Emilia.

Display case:

- Plant fiber basket and bark containers from the indigenous people of Tierra del Fuego, 19th century, Civic Museum of Modena, Boccolari donation.

- Bone spear points, Tierra del Fuego, 19th century, Civic Museum of Modena, Boccolari donation.

- Shark and whale teeth collected by Francesco Giuseppe Tozzoni near the Magellan Strait, 19th century, Imola Museums, Palazzo Tozzoni.

Monitor

“During this stop, a canoe of savages came to our board, [in which] there were two men, one woman, four children and a dog. The woman, with the smallest children in her lap, steered with an oar and the men rowed. In the middle of the canoe a fire burned.”

From the diary of Lieutenant Enrico Serra

Wooden oar. On the tag: “Taken in a canoe of savages from Tierra del Fuego in the Magellan canals the year 1882 by F.G. Tozzoni”, 19th century, Imola Museums, Palazzo Tozzoni.

4 Arrival in Peru

On 13 March 1883, the Corvette Vettor Pisani reached the Italian naval station in the Pacific, in the harbor of Ancon on the central coast of Peru. The presence of naval units in this country was particularly opportune given the ongoing conflict with Chile for the possession of guano and saltpeter deposits. The Chilean army imposed taxes and plundered the property of Italians, who asked the Italian Navy for protection.

In Ancon, Boccolari and Parenti had the opportunity to explore the large pre-Columbian necropolis that extended to the dunes near the beach, where they collected human remains and archaeological material, which, upon their return to their homeland, they donated to the Civic Museum of Modena.

5 The necropolis of Ancon

The necropolis of Ancon extends over 68 hectares. Its use as a cemetery area began around 600 BCE and ended with the Spanish conquest of Peru in 1532. It is therefore within this chronological timeframe that the human remains and archaeological materials displayed in this exhibit fall. The tombs of Ancon were pits dug into the ground, closed with roofs of matting or reeds. The almost desert-like nature of the terrain favored the natural mummification of the bodies, which were buried in a crouching position inside wrappings made up of multiple layers of fabric known as bundles. Only a limited part of the necropolis was the subject of systematic excavations in the twentieth century. The results of this research, published only in part, complement the information obtained by the German geologists Reiss and Stübel during their 1875 excavations.

6 From 3D to computer graphics reconstruction

Face reconstructions are applied in forensic contexts but they are also frequently used in the historical-archaeological field to restore to the remains of men and women of the past a part of their identity. The reconstruction takes place starting with Computerized Tomograhpy (CT), which makes it possible to obtain a 3D copy of the skull. This is then imported into 3D software to model muscles and skin in a virtual environment. The reconstruction of the mummy’s face was the starting point for the evocative video installation dedicated to the “girl from Ancon”.

Female mummy. Presumed age of death 16-18 years.

Under the body there are remains of the wrapping that constituted the funerary bundle. The skull presents an intentional oblique tabular deformation. The autopsy exam revealed a fracture of the hyoid bone, a nearly unequivocal indication of a violent death caused by strangulation. It is likely that this was a ritual sacrifice, a practice that was widespread in the Central Andes in pre-Columbian times.

Necropolis of Ancon, late 13th—early 15th century, Civic Museum of Modena, Purchased from Paolo Parenti.

7 The tattoos

Investigations with a digital imaging technique have made it possible to identify marks on the mummy’s body that are barely visible with the naked eye and can be attributed to tattoos. Both forearms feature a pattern of motifs with stylized figures of fish and birds that were part of the marine ecosystem that regulated the life of the inhabitants of Ancon. Other symbols are present on the back, and near the right eye there is a diamond-shaped mark. In the necropolis of Ancon, there have been several cases attested of women with tattoos on their arms and around their wrists, accompanied by grave goods that seem to allude to a social distinction of the deceased.

8 Peoples of Ancon

When Boccolari and Parenti visited Ancon in 1883, the necropolis appeared as a vast expanse of sand from which human remains emerged, brought to light by previous excavations and abandoned on the ground. Skulls and bones dismembered from the body could be collected from the surface during a simple “archaeological walk” such as the one carried out by the two travelers from Modena. The Boccolari-Parenti Ancon collection includes eight skulls. Their study, along with that of the mummy, made it possible to specify the sex of the deceased and the presumed age at the time of death, and to identify aspects linked to the daily habits of the people of Ancon and to the funerary ritual.

On the wall: Female individual. Presumed age of death 40-49 years.

She presents an oblique tabular deformation of the skull. The deformation was obtained by exerting pressure with wooden boards and various ligatures on the heads of newborns in the first few months of life. By varying the pressure and the type of bindings, different shapes were produced which represented a marker of social identity. The study highlighted intense stress on the masseter muscle, responsible for the chewing action, perhaps attributable to the chewing of corn for the preparation of chicha, an alcoholic beverage used at parties and in ceremonies.

On the wall: Male individual (DNA undeterminable). Presumed age of death 30-39 years.

Oblique tabular deformation of the skull.

The study highlighted intense stress on the masseter muscle, responsible for the chewing action, perhaps attributable to the chewing of corn for the preparation of chicha, an alcoholic beverage used at parties and in ceremonies.

On the wall: Female individual. Presumed age of death > 50 years.

Oblique tabular deformation of the skull.

On the wall: Male individual (DNA undeterminable). Presumed age of death 40-49 years.

Oblique tabular deformation of the skull.

The study highlighted intense stress on the masseter muscle, responsible for the chewing action, perhaps attributable to the chewing of corn for the preparation of chicha, an alcoholic beverage used at parties and in ceremonies.

Traces of auricular exostosis were detected, a condition which can develop as a consequence of repeated immersion in cold water, likely due to immersion fishing activities for the collection of shellfish.

On the wall: Male individual (DNA undeterminable). Presumed age of death 20-29 years.

Oblique tabular deformation of the skull.

The study highlighted intense stress on the masseter muscle, responsible for the chewing action, perhaps attributable to the chewing of corn for the preparation of chicha, an alcoholic beverage used at parties and in ceremonies.

On the face and head, analyses highlighted remains of cinnabar, a substance of mineral origin (mercury sulfide) from which a bright red powder was obtained, which was then spread for ritual purposes on the faces of the deceased and on objects considered sacred. On the head there is a thin brown cotton fabric covering raw cotton padding.

On the wall: Individual presumed to be male (DNA undeterminable). Presumed age of death around 7 years.

Oblique tabular deformation of the skull. Placed on the head is a small crown made of cotton threads wrapped around a core of human hair.

On the wall: Individual presumed to be female (DNA undeterminable). Presumed age of death around 5 years.

Oblique tabular deformation of the skull. On the face there are traces of cinnabar, a substance of mineral origin (mercury sulfide) from which a bright red powder was obtained, which was then spread for ritual purposes on the faces of the deceased and on objects considered sacred.

On the wall: Female individual. Presumed age of death around 2 years.

On the head there is raw cotton padding covered by a very dirty and deteriorated striped cotton canvas.

9 A community of fishermen

The populations that for hundreds of years buried their dead in the necropolis of Ancon lived in dwellings made of reeds and matting. In fact, the excavations did not reveal any remains attributable to buildings. The main resource of these communities was fishing, which was practiced by the men, as also attested by the numerous nets and fishing tools associated with male individuals buried in the necropolis. Fishing products were part of a trade network with communities of the nearby river valleys, from whom the inhabitants of Ancon obtained agricultural products such as corn, beans and pumpkins.

Display case:

Fishing net, lines and lead weight, Necropolis of Ancón, 9th—early 16th century, Civic Museum of Modena, Boccolari-Parenti Collection.

10 Weaving

Entrusted to the women was the practice of producing fabrics that in the Andean world had a function that went beyond that of a simple garment and affected the social and ritual sphere as an important indicator of status and ethnic identity. The offerings of fabrics marked the main stages of the individual life cycle, from birth to marriage to death. On the coast the fabrics were made from cotton of varying natural shades, from white to beige, brown and blue. Alpaca wool imported from the plateau was used to make multicolor borders.

Monitor

Details of fabrics from the Boccolari-Parenti Collection

Display case:

- Skeins of blue cotton and yellow-dyed alpaca wool, balls of white and beige cotton yarn.

- Weaving sword.

- Cactus thorn needles, some of them with eye.

- Striped canvas in various natural shades of cotton.

Necropolis of Ancón, 9th—early 16th century, Civic Museum of Modena, Boccolari-Parenti Collection.

11 Funerary bundles

Funerary bundles were made of multiple layers of fabric interspersed with raw cotton padding and leaves. Offerings of ceramics, fabrics and objects related to the activities carried out by the deceased during his lifetime were placed between the layers of the bundle and around it. Between 600 and 1000 CE, the bundles were completed by a false head made of wood or textile, which probably simulated the face of the deceased. (On the wall: Funerary bundle and false heads from the necropolis of Ancon, Reiss, Stübel Excavations, 1875).

Display case:

- Two terracotta female figurines, probably linked to fertility. They were wrapped between the bands of the bundle or hung with cords passing through the holes in the headdress. Necropolis of Ancon, 13th—15th century.

- Ornamental plume for false head made from albatross feathers and plant fiber. Necropolis of Ancon, 10th—12th century.

- Earrings for false head made of small cane tubes wrapped in plant fiber. Necropolis of Ancon, 10th—12th century.

- Cane crosses wrapped in cotton threads. They were placed as ritual offerings in the tomb beside the bundle, 10th—12th century.

- Cotton envelopes used as ritual offerings in the tomb. Necropolis of Ancon, 10th—12th century.

- Spondylus valve used as funerary offering in the tombs. Spondylus is not found along the coasts of Peru and was imported to Ancon from the coastal regions of Ecuador. Necropolis of Ancon.

Civic Museum of Modena Boccolari-Parenti Collection.

12 Late-era funerary bundles

Around 1000 CE, the false heads become more rare and less elaborate, until they disappear entirely in the late phases of the necropolis (13th—16th century), when the bundles consist of simple wrappings of plain or striped cotton cloth tied with rope bindings. A simple bundle of this type wrapped the body of the “girl from Ancon”.

On the wall: Late-era funerary bundle from the necropolis of Ancon, Reiss, Stübel Excavations, 1875.

Display case:

Funerary offerings connected to the ritual consumption of coca leaves:

- On the left: woolen purse for holding coca leaves, Necropolis of Ancon, 10th—12th century.

- On the right: woolen purse for holding coca leaves, Necropolis of Ancon, 10th—12th century.

- Lime-holder gourds with dipper. Lime was used to dissolve the stimulants contained in the coca leaves. Necropolis of Ancon, 13th—16th century.

- Small cane tubes containing lime. They were inserted between the fingers and toes of the deceased. Necropolis of Ancon, 13th—early 14th century.

Civic Museum of Modena Boccolari-Parenti Collection.

Display case:

probably belonging to the funerary objects of the mummy:

- Cotton band with decoration with squared volutes obtained by untying wires of white warp on a blue background.

- Fragment of styled fabric red and yellow checkered chancay with additional wool wefts on a cotton warp.

- Rectangular striped cloth in different natural shades of cotton.

- Spindle with wooden spindle and used ceramic bowl to spin 13th—early 14th century.

Necropolis of Ancon, Civic Museum of Modena Boccolari-Parenti Collection.

On the wall:

Chancay-style amphora with figures of cormorants in relief. Necropolis of Ancon, 13th—15th century, Civic Museum of Modena Boccolari-Parenti Collection.

On the wall:

- Anthropomorphic jug depicting a feminine figure. Necropolis of Ancon, 10th—11th century.

- Chimú style pottery produced on the northern coast of Peru.

- Vase with conical necks joined by a ribbon handle.

- Dog-shaped vase. Necropolis of Ancon, 13th—15th century.

Civic Museum of Modena Boccolari-Parenti Collection

On the wall:

- Chimú-Lambayeque style ceremonial vase in the shape of a boat. A human figure with an oar in his right hand is modeled on the bow. Necropolis of Ancon, 12th—13th century.

- Chancay-style amphora with black painting on white background. Necropolis of Ancon, 13th—15th century.

- Amphora for chicha. Chicha is a drink obtained from fermented corn that is still consumed today at parties and ceremonies in the Andean region. Necropolis of Ancon, 13th—15th century.

Civic Museum of Modena Boccolari-Parenti Collection